“To my mind it is crucial to be able to both propose and seek opportunities to incorporate art, in any form, into our daily lives”, says Italian fashion mogul and collector Luciano Benetton.“We need it more than ever in these difficult times.”

When you mention Benetton’s name, the first images that comes to mind are colourful, cheeky pullovers, artfully photographed by controversial fashion photographer Oliviero Toscani. What is less known is that the Italian businessman is a collector with a huge vision: that of mapping the entire world artistically.

Dubbed “Imago Mundi”, his collection and world-wide project spans from New Zealand to Burkina Faso, covering more than 160 countries for a total of 26,000 artworks. For its huge proportions, the ever-expanding collection incorporates a number of sub-collections, and features especially commissioned works in a standard format of 10×12 cm.

LARRY’S LIST spoke with Luciano Benetton to ask him about his utopian endeavour and his views on art.

What made you want to start collecting contemporary art?

I have always tried to make time to visit artists or art galleries during my business trips. Connecting with art in different countries has enabled me to better understand the characteristics of a community, particularly if it is far from us, both in terms of physical distance and its customs and traditions.

Can you tell us the story of the encounter with the artist that inspired you to start the Imago Mundi Collection?

I visited Miguel Betancourt’s studio during a trip to Ecuador. At that time, my encounters with art between one business appointment and the next were always a bit hasty, so I asked him for a business card to allow me to take a more detailed look at his work later. In an act of generosity, in place of a card, he gave me a small 10 x 12 cm canvas painted in oils. Having seen my amazement at the quality of the work which, despite its tiny size, brilliantly expressed the artist’s style, my associates in South America later presented me with over 200 works created by South American artists, all in this particular format. I was fascinated by the way these miniature artworks were capable of embodying so much beauty. I decided to thank the artists with an exhibition, in Santiago de Chile in 2008, and with a catalogue, Ojo Latino, the first of a long series in the Imago Mundi Collection which today comprises over 160 volumes.

How does Imago Mundi differentiate itself from your private collection?

As far as my private collection is concerned, at times I have followed my instinct, buying works on my travels simply because I liked them or because they evoked memories and emotions; in other cases, I have relied on gallery owners, particularly for American and Japanese art.

How did the idea to map the entire globe, as well as local communities, expand over time?

When I decided to undertake this project, I already had in mind a mapping that would include not only the artistic production of the different countries but also that of the many native communities that express their own, not only visual, culture. One of the first collections was dedicated to Aboriginal Australians and for the role of curator we found a special man, an “initiate” as he is known, with knowledge of the indigenous languages, who managed to involve nomadic groups in the project. It was challenging but the results were incredible. Other examples include the Inuit, with their stone sculptures, or the Pygmy population of the equatorial forest, or again, the Kalahari Bushmen. Among many others, I am particularly proud of the work done with the collection dedicated to the Kurds which brought together artists living in four different countries (Turkey, Iraq, Iran and Syria) and others who have made the choice to live around the world. This collection also required a great deal of effort in the linguistic editing of the catalogue: in fact, the texts, in addition to being in Italian and English, are also in two Kurdish dialects.

Indeed, Imago Mundi has many different collections within the main one, and you rely on local experts to select the artists. Do you have a specific process when you decide to engage with a new artistic community?

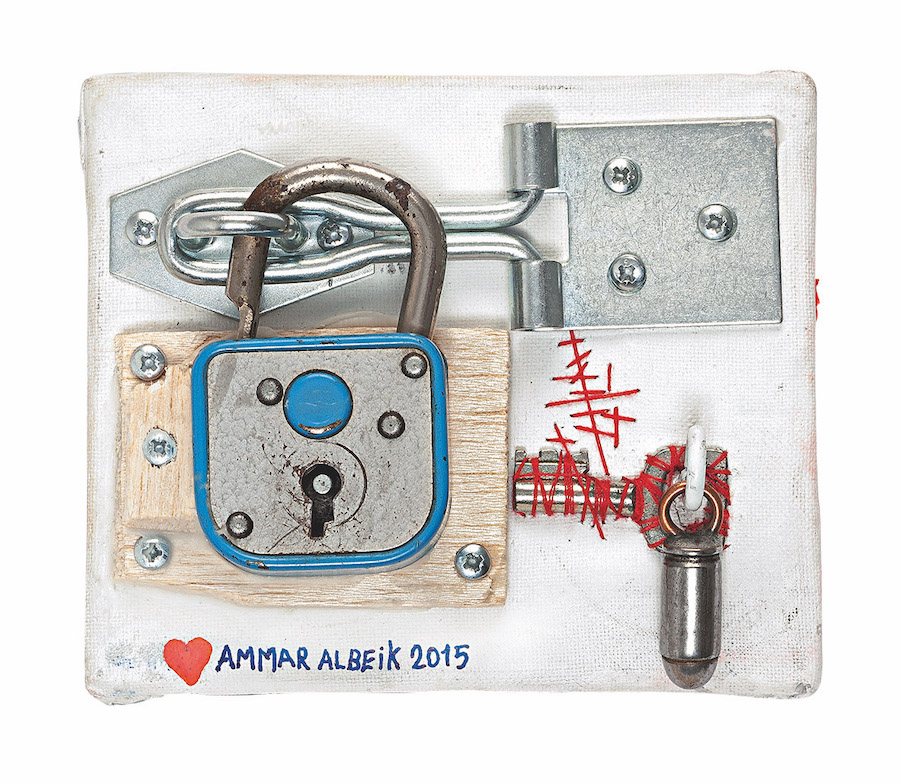

It has been a long and exciting process of teamwork, with very special encounters; a word of mouth between protagonists of the global creative community. We have had to overcome numerous obstacles, especially in countries with nomadic populations, such as Algeria and Morocco, which have around 300,000 people living in exile in the desert. In the case of the Syrian artists, it was very difficult to obtain their works with much of the country under bombardment. Thanks to some Syrians who were in London however, and others in Libya and Lebanon, we were able to receive 35 short videos via the internet for the collection; these were really special. We obtained the Somalia collection with the help of the Red Cross. There are many more examples like these.

In your collection, you give equal relevance to emerging or renowned artists. Why do you take this approach?

I have always thought of the Imago Mundi Collection as a non-profit and democratic contemporary art project that had to involve — as I touched on before — countries with a less favourable economic or political situation than ours. Above all, it could and should give visibility to the many new talents who, time and again, have provided and amazed us with works abounding in creativity, energy, enthusiasm, and even a desire for redemption, like the young African artists.

You often meet in person the artists you collect. How important is it for you to meet the artists who created the artwork?

Being able to meet the artist directly is a great privilege, and I try to do so whenever I can. An artist who tells me about themselves conveys nuances that bring a new dimension to their work. I have met a number of the artists at the Imago Mundi exhibition inaugurations, that we have organized in various countries, but I certainly cannot say that I know many of them.

What is your most treasured artwork?

There are many examples of particularly special works. I was struck by the creative poetics and spirit that animate the artwork of the artists of the Weya community, a small village in the mountains of Zimbabwe where a group of women, mistreated and exploited by their husbands, have found refuge, independence, and freedom in making art. Other examples include the extraordinary techniques of the Japan collection, or the works in the Visual Poetry catalogue, a rare and extraordinary European collection.

You have displayed parts of your collection in many different locations around the world. What has been one of the most rewarding exhibitions for you?

Among the many, I would like to mention three: the “Mediterranean Routes” exhibition, a homage to beauty and at the same time to a hope for communion among the countries that inhabit the Mediterranean basin. It took place in Palermo, Italy, and represented all the collections of the countries bordering the Mediterranean, from Greece to France, through the nations on the coast of North Africa: Tunisia, Algeria, Libya, for example, up to those on the Adriatic, alongside Syria and Lebanon and, of course, Italy. A dialogue among 21 collections and over 3,500 works, in which the creativity of its people expressed the cultures, traditions, and beauty of a sea that unites, but which has also sadly become synonymous with barriers and desperation.

You also have a space, Gallerie delle Prigioni, in your native town of Treviso, Italy, and in your shows there, like the recent “When the globe is home”, you explore how art mediates between the concepts of “home” and “the world.” What’s the importance of being a “glocal” collector today?

Since the beginning of my entrepreneurial adventure, I have been asked why I hadn’t considered leaving Treviso and choosing a more international city, such as Milan, as the base for our headquarters. My response is that as I wanted to travel the world, a small provincial town was not a limitation; it offers many advantages over a large metropolis, all I had to do was hopping on a plane. I think it is a basic imperative to understand, support, and enrich the cultural aspects of one’s hometown. A constructive opening towards the world can only come from an awareness of who we are.

Did the pandemic shift your way to map the art world in any way?

Like everyone, we have had to reconsider our agenda. The pandemic prevented some exhibitions from going ahead of course, both at the Gallerie delle Prigioni and abroad; we had planned, for example, an exhibition in Tokyo in occasion of the Olympics that should have been held in 2020. Instead, we have used this time to focus our initiatives and investments on the web in order to consolidate our artistic community by reaching out on social media platforms and through our portal, which we will soon present with a new layout that we hope will be increasingly stimulating and open.

What is your motivation behind opening a public accessible art space?

It has always been important to me to open cultural spaces to the local community and surrounding area; the Benetton Foundation established in 1987 is an example. With the development of the Imago Mundi project, it was a natural progression to find a dedicated space for it, so in April 2018 we inaugurated the Gallerie delle Prigioni and, the following year, the Fondazione Imago Mundi was established. These steps have given new impetus to the entire project. The Gallerie delle Prigioni — so called because they are housed in an historic prison from the Habsburg era, expertly restored by the architect Tobia Scarpa — provides an exhibition space dedicated to contemporary culture, a platform for experimentation which, from the starting point of the Imago Mundi Collection, hosts exhibitions, seminars, and workshops, open to all disciplines of artistic exploration.

What is your advice to young and fresh collectors?

I think I would recommend being curious. I believe that curiosity combined with passion creates the right chemistry to form a critical thought process in total freedom. It is seemingly hard to know how to behave in the context of contemporary art, but I always keep in mind the fact that the great artistic movements of the last century, or of the past in general, were contemporary in their own time. Again, I think instinct, curiosity, and a good deal of research can be of great help.

Related: Imago Mundi Collection

Instagram: @fondazioneimagomundi

A selection of artists Luciano collects:

Ammar al Beik

Elizabeth Muwungani

Miguel Betancourt

Tommy Watson

Walid Siti

By Naima Morelli