Chinese entrepreneur Liu Lan has been building up an art collection for over 25 years. Currently with around one hundred pieces of artworks, her collection covers some of the most representative artists of Chinese contemporary art, such as Zhang Xiaogang, Liu Ye, Song Dong, Xu Zhen, to name a few. In 2020, Liu Lan founded “The Room” in Beijing and began exhibiting her collection there. In Liu Lan’s view, an art collection needs to be carefully nurtured, “otherwise it will wither”.

LARRY’S LIST talked with Liu Lan about her motivation to set up “The Room”; upcoming plans for this space; her interest in video art, her favorite private museums in the world, and the three most important factors in collecting.

You built “The Room” in 2020, how did you decide on the theme for the first exhibition? Did you face any difficulties at the beginning?

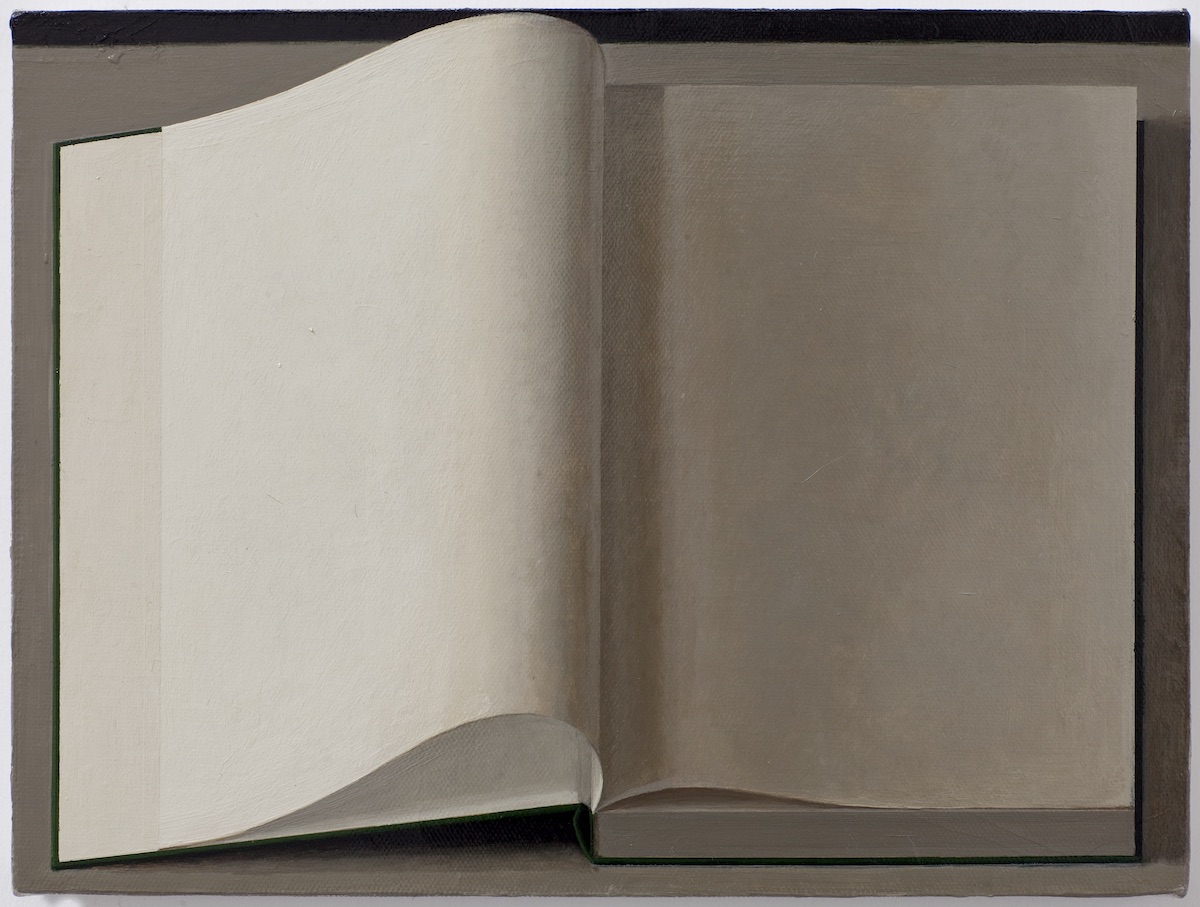

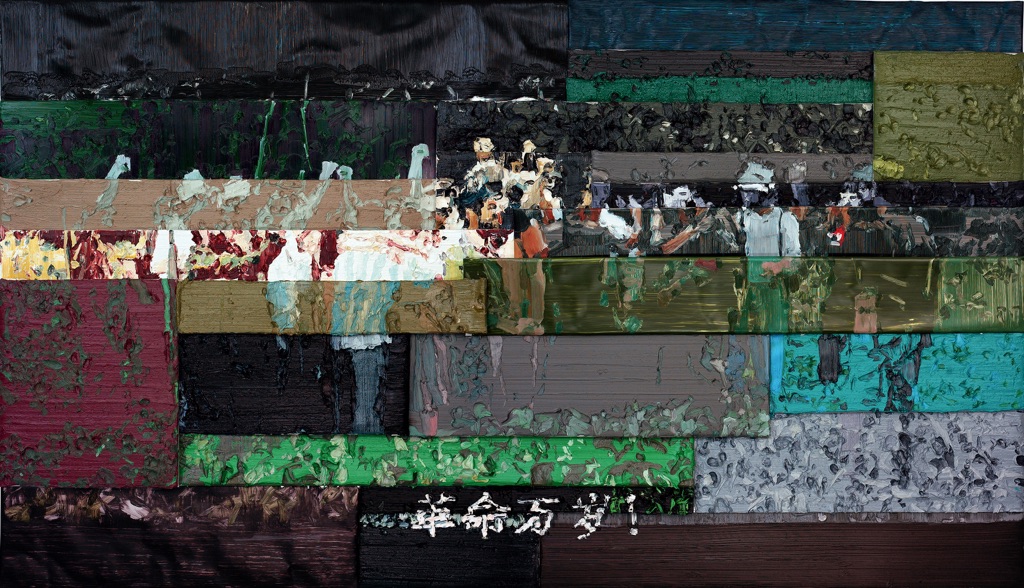

The space was not yet equipped with the heater, so it was very cold! Everyone worked very hard. The works I chose for the exhibition were those that resonated with the times. On the ground floor were works by Xie Nanxing and Wang Guangle. On the lower level was Song Dong’s “One Table, Two Stools”, a commissioned work for the space. On the opposite side was a painting by Zhang Xiaogang, the colours echo each other. As this space is called “The Room”, I think the main idea of curating the show was around the concept of the room. A room represents a private space, and my collection is also private. So the theme of the first exhibition was mainly around privacy and individuality.

A collection is like a string of pearls. Each piece corresponds to different stories. It starts as separate pieces, as different individuals, or as one after another. But in fact, the longer I collect, my concept of how I can string these “pearls” together became stronger. I hope to create dialogues between the works.

It was a very impressive exhibition. The works on display had a very strong sense of interaction with the space.

In the old generation, it was very difficult to get intellectual nourishment. When one day you see artworks that condense that past generation, it would have a very strong impact on you. Just like Song Dong’s previous exhibition at MoMA in New York, “Projects 90: Song Dong”. Another example is his work “One Table, Two Stools”, both inspired by a time of material poverty and reconstructed with his own personal aesthetic.

How many pieces do you own in your collection?

Over a hundred pieces, each piece is carefully selected. Good works are scarce and you don’t come across them every day.

What are the following plans for “The Room”?

The next exhibition in “The Room” is “Feminine”. “Feminine” does not necessarily mean femininity; men also have a feminine side and women also have a masculine side. French words are divided into two categories: feminine and masculine. Many words that we think may be more masculine are feminine in French. Contemporary art is very much concerned with gender expression. With this next exhibition, I want to string together in a narrative thread what I have in my collection about gender, about what is feminine. By doing this kind of thematic exhibition, I am actually playing the role of artist and curator.

Is there any work that you saw at the time that produced a completely different feeling from when you saw it again a few years later?

Song Dong’s “A Pot of Boiling Water”. It started as performance art that took place in a hutong(alley). Song Dong poured this pot of boiling water on the ground, and his wife Yin Xiuzhen recorded the process and took a series of photographs. I collected this work as nice photographs to look at and put it in my tea room. A few years later, I realised that what he was trying to convey was that nothing in this world can be grasped, everything is fleeting. This is a whole different feeling from when I first saw it. The artwork that moves me never stays the same.

You mentioned your meeting with Song Dong during the pandemic outbreak. So is it important for you to meet artists in person?

We met during the epidemic, in a hotel where not many people were staying at the time. The hotel had similar atmosphere and décor as that Kubrick’s film “The Shining”. There was a small garden next to the hotel where you could see a little bit of sunlight, which gave a particularly uncanny feeling. The conversations in The Room’s exhibition catalogue took place in that environment and were a true reflection of the artist’s state of mind. Having the opportunity to talk to artists is very precious to me.

What are the main sources for you to buy works? How do you feel about the art market has changed over the years of collecting?

In the early days of collecting, I bought most of my collection (60%) from the secondary market. It was common for works by artists who are hot today to go unsold and unappreciated back then. There is a saying that Chinese contemporary art accomplished the collector, I disagree with that. Twenty years ago, although many good works were selling at very low prices on the secondary market, there were even fewer collectors with the guts and ambition to do so. Only a very few discerning people at the time could realise that Chinese contemporary art would become an international art scene.

Does that mean that when you first started collecting you didn’t necessarily think about the circulation of these works?

No, I didn’t think about the circulation of the artworks at that time, it was mainly a matter of appreciation. There’s a lot of uncertainty in investing in art, and it’s that uncertainty that you’re buying. Investing is also a contest of vision — a contest that started 20 years ago.

Do you collect non-traditional mediums, such as digital art?

I have been collecting video art. People who are not familiar with the history of Chinese contemporary art don’t necessarily collect video art, but in fact, video art is one of the most important categories in Chinese contemporary art. Maybe sometime later “The Room” will do an exhibition on video art.

Are there any emerging artists you’ve been following lately?

One of the artists that I have been following recently is Ge Yulu. He does installations, videos, and performances. For example, in the work “Love Letter”, he used a blower to blow a love letter to Beijing. There are many simple and unadorned expressions of emotion in his works. He also uses a kind of humour to relieve the pain in life or some stereotypical rules. I think we need such a sense of humour, which challenges what is solidified in our tradition.

This is what a lot of new media art is doing, breaking the traditional rules.

Yes, I also have a video work by Zhao Bandi in my collection, “One Man’s Olympics”. The whole video is of the artist running alone, through all the cities, roads, and alleys. At the end of the run, he organised a fictional opening ceremony of the Olympics in Bern, Switzerland. I feel that Zhao Bandi’s work is somehow similar to that of Ge Yulu. They both embody the feeling of a person struggling with the absurdity of reality. It conveys a very strong sense of loneliness.

Having collected so far, have you come across any very good, but relatively unknown, artists or works?

While contemporary Chinese art has always seemed to be a relatively buoyant market overall, I think some 20th-century Chinese-French artists are completely underrated. This group of artists did not experience the cultural discontinuity of the new China. They experienced traditional Chinese private schooling, and they absorbed the ways of thinking of the Western cultural system. This is why you can see the coexistence of both cultures in their works, which are very rich in connotation. I hope to present a thematic exhibition on this subject in due course.

By talking to you, we realise that collecting art is a complex thing. Apart from money, art collecting also requires experience and time. Is it easier to collect with an eye that is not swayed by profit?

Collecting is not a career for me, but a hobby. I cherish this freedom. At the same time, collecting needs to be in a positive cycle, any good collection needs to be updated constantly. Good things are rare, like diamonds.

I think the older generation shouldered a sense of responsibility for the times. Young people nowadays don’t have such a strong sense of it, so they don’t use art as a sentimental attachment. I think this is a good thing.

In the last ten years, China has seen an exponential change from twenty years ago in terms of the number of new galleries, private galleries, as well as art fairs and auctions, especially with the emergence of many young collectors. How do you think young collectors are different in comparison to the previous generation?

In all the years I have been collecting, I am not really concerned about the scene anymore. No matter how this market changes, I stick to my own taste and my original intention. Art collecting is about finding what remains the same in the midst of change. NFT, trendy art, there is a plethora of new things coming out under the banner of art. There is a lot of fast-moving consumer goods in contemporary art. I think people who collect this kind of art don’t necessarily want to support contemporary art, but use art as a financial product to invest in. Art must have circulation, but art collecting is not speculation.

Can you share some of your favourite private art museums around the world?

In Beijing, of course UCCA cannot be replicated. Also, whenever I go to Shanghai, I would visit the Long Museum and Rockbund Art Museum. The quality of exhibitions at these two museums is very high.

My favourite private art museum overseas is the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia, USA. They have a great collection of Impressionist paintings. I spent over ten years in France and saw quite a lot ofImpressionist exhibitions during that time. However, it was the exhibitions in America that really made me fall in love with Impressionism.

What are the three most important factors in collecting art for you?

Personal preference, having a narrative, and having circulation. All three must be present. The work must have circulation, otherwise the collection will wither away.

Do you have the feeling that it’s freer to look at art when you’re working not in the art industry?

I don’t work in the art industry, which I consider to be fortunate. Art stays with you for a long time in your life. It is your companion. What makes art history relevant is that it is all connected to the history of human society. It is in a big macro context that you look deeper into the subject. If you look at art from the perspective of a hobby, then everything seems different again. So I feel very lucky that I can be completely free.

A selection of artists Liu Lan collects:

Liu Wei

Liu Ye

Song Dong

Xu Zhen

Zhang Xiaogang

By Tyra Wang and Ballad Liao