Living and working between Accra, London, and Plettenberg Bay in South Africa, Joseph Awuah-Darko, also known as Okuntakinte, is a British-born Ghanaian contemporary artist, curator, social entrepreneur, and art collector. Also founder and Director of the Noldor Artist Residency, and President of the Institute Museum of Ghana in Accra, he is regarded as a leading figure in the scene of contemporary emerging artists from Africa.

LARRY’S LIST had a chat with Joseph who explained why gender parity is important for him and his art collection, why it is crucial to meet in person the artists whose work he collects, the art-world pet peeve in his opinion, and why friend and architect David Adjaye has inspired him the most. He also shared three emerging African/African diaspora artists to watch out for.

Collecting

What made you start collecting art? What is the main motivation behind your collecting?

In the sense that it was sparked by great friendships with dynamic African contemporary artists, the motivation to begin collecting was truly organic. One of my very first visits to Serge Attukwei Clottey’s studio, where his wife Awo is also an artist and a dear friend, took place nearly six years ago. I was able to immerse myself in the community where Attukwei’s famous yellow tapestries were made, which helped me learn more about his work and philosophy. Intimate studio visits in my early years of collecting till now have laid the groundwork for subsequent acquisitions. It has been an honor for me to visit the studios of many great artists, including Sir Isaac Julien, Kaloki, Salah El Mur, Foster Sakyiamah, Zizipho Poswa, and Maku Azu; all of the artists whose works I am happy to live with and would consider to be dear to me.

When did you fall in love with a piece of art? What was it?

The most recent time I fell in love with a piece of art was a wooden triptych ‘Les Perfectionnés et le sacrifice de maturité’ by Ivorian Assoukrou Aké. I first saw the work in Paris last year at AKAA [Also Known As Africa] art fair while visiting with my Chief Curator at the Institute Museum, and we were both stunned. I admired the depth of his existential lucid carvings on these blackened panels brewing with symbolism and meaning. He had just been awarded the Ellipse Prize in Paris for 2022. And I am very happy to have not only acquired the work for the museum but two additional pieces from Galerie Cécile Fakhoury this year.

Why do you focus on collecting African contemporary art?

I have often gravitate towards works that speak inherently to the past, while also looking attentively towards the future all within the context of the Africa. My role as custodian of exclusively African Contemporary art is simply informed by the fact that I identify with many of the themes explored by the artists from a lived experience perspective. Issues surrounding neo-colonialism, migration, self-actualization, mental health, and community have all been thematic elements that have informed my own existence—so there is a resonance with the work that is real and not contrived. Like any seasoned collector, I am also uniquely invested in the stories of all the artists I have supported through building friendships; sacred studio-visits, Zoom catch-ups and hearty meals shared, all form part of the larger dialogue in the way I relate with artists. There is a sense of oneness that always drawn me to focus on collecting artists from Africa who may otherwise have been overlooked in the wider context of the contemporary art ecology.

What style of art that has consistently attracted you? Or what is the theme that unites all the works you have acquired?

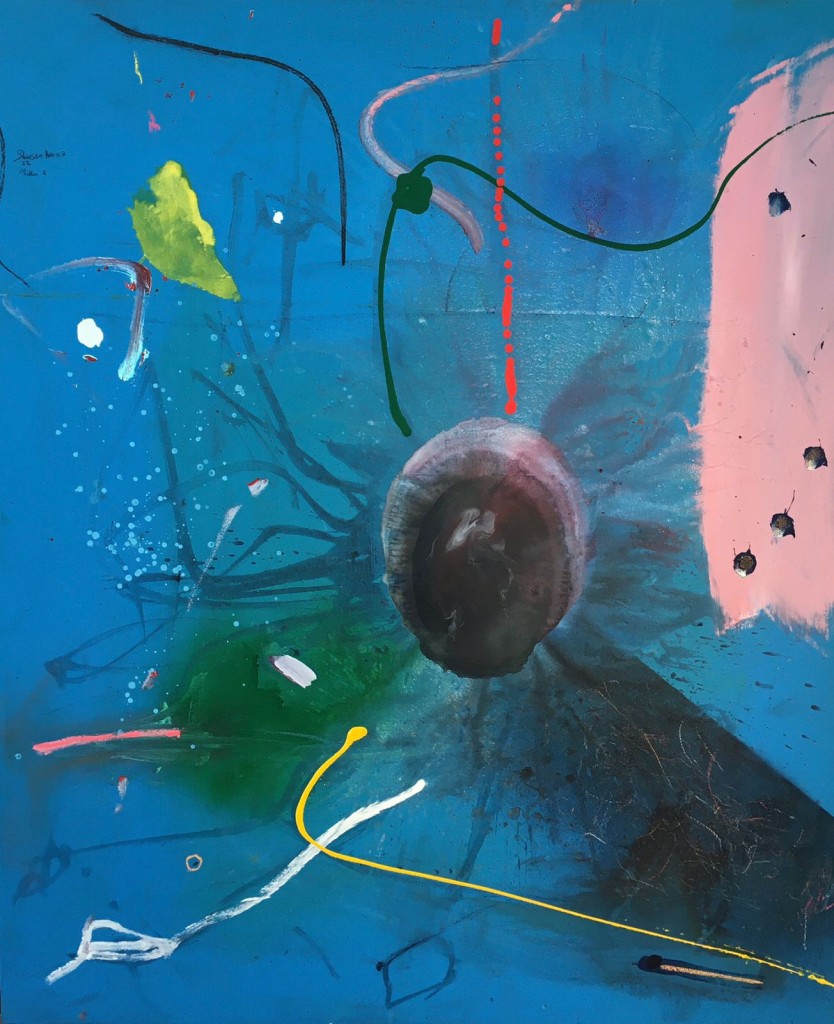

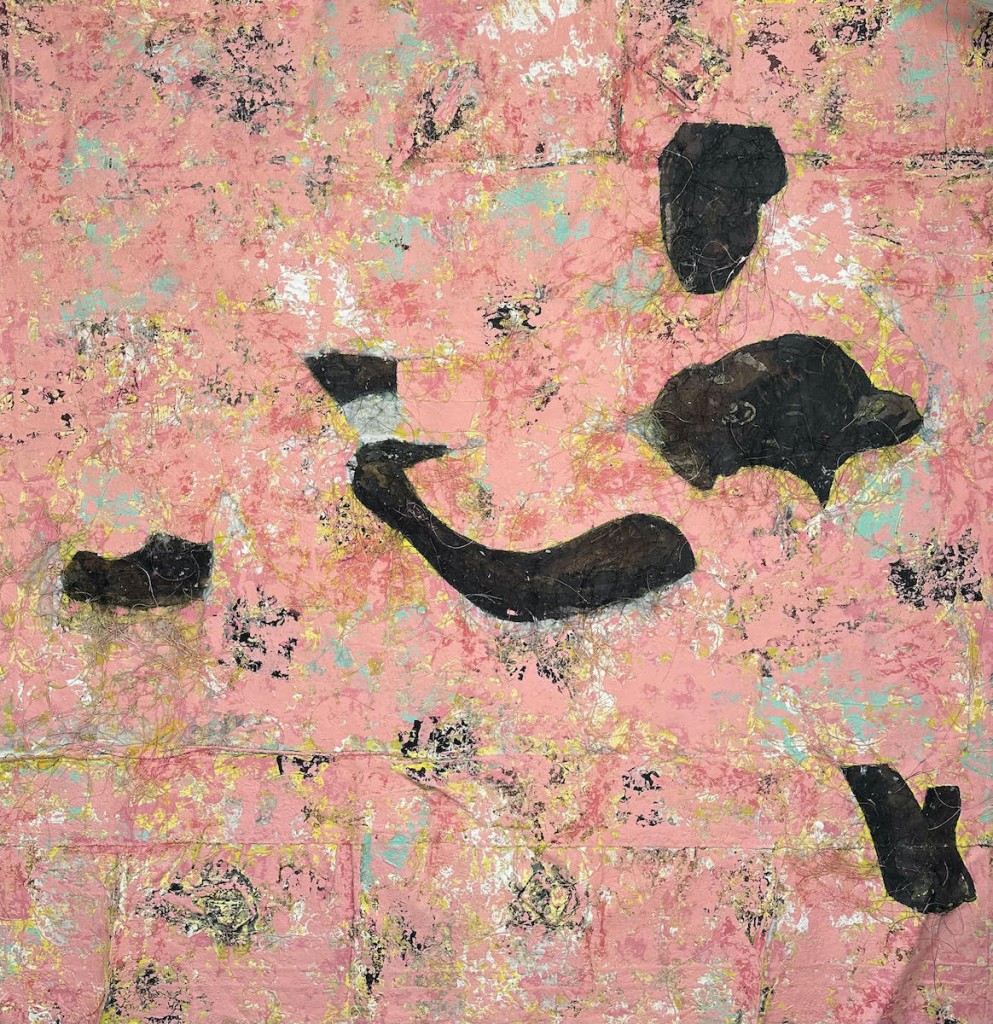

I wouldn’t say I am drawn to any specific or style; there is a focused eclecticism to how I collect. The works tend to cut across artistic disciplines be it tapestry, sculpture, or painting. And even within painting, my focus ranges from abstraction, such as the work of Araba Opoku; to figurative surrealism, such as the work of Sthenjwa Luthuli or Elizabeth Sakyiamah. What definitely cuts across is the unapologetic uncensored sense of identity captured within each piece in a distinctively cross-disciplinary sense. Photography also holds a special place within my collection, and Derrick Boateng’s work in particular has this effervescent, saturated color indicative of the ubiquitous, vibrant nostalgia of Ghanaian life. One of his works which hangs in the house, a rare series in collaboration with Louis Vuitton, just makes me smile.

What were the first and the latest artworks you purchased?

The first artwork I ever seriously purchased must have been a piece by the Kenyan artist Michael Soi, whom I had the esteemed pleasure of meeting during his residency at Gallery 1957. The political discourse and satire surrounding his practice was something that truly excited me; it felt like a kind of provocative anthropological study. On the other hand, the most recent piece I have ever acquired has been a clay terra cotta “siren” sculpture by Seni Awa Camara, the Senegalese artist who started her practice in 1983 exploring mythological deity. It is currently at home at Plettenberg Bay in South Africa in a very cherished part of home.

How many artworks do you own? Where do you display your collection?

There are well over 200 works within my private collection spread across homes in Accra, London, South Africa, and France. It is a joy to have pledged some of these works to the Institute Museum’s archive where they are periodically displayed.

Have you ever presented, or would you wish to present, your art collection publicly?

Part of the collection is periodically displayed at the Institute Museum of Ghana, and I have expressed an openness towards loaning work to museums and other institutions internationally.

And why is gender parity important for you? What is the proportion of male and female artists in your collection?

The answer to this is quite simple. Gender parity matters because women artists are largely underrepresented throughout art history especially in the context of African art. I wanted the collection to address this subdued reality and be part of the solution in some small way. The proportion of males to females in this collection is almost perfectly 1 : 1 (with a few anomalies), and it is something I am proud of.

What considerations guide you to make a purchase?

Something I truly consider in all truism beyond the quality of the work is if I really believe in the future and longevity of the artist’s career. So based on varied factors from the gallery program the artist is with, the residencies they have attended, and the nature of their existing collectors, I can decipher in a present or potential status scenario if a work is worth purchasing. It is also very important to understand that the way I collect for my private collection is not the same way I would collect for the museum collection. Both sensibilities and processes are independent of each other in a wonderful way.

Through what channels do you discover African contemporary artists or artworks?

I typically discover artists through intense studio visits, referrals, Instagram and gallery newsletters, in that order.

How important is it for you to meet the artists who created the artwork?

For me, it is often crucial to meet the artists in person because it is an opportunity to build a connection and a friendship that allows you to humanise the artist beyond their ability to create work. I always say that artists are not humanised enough in the art world as fully living people with concerns and families and even aspirations. So for that reason I find it necessary to meet the artist. Additionally, it is also important to get a sense of an artist’s approach to building a body of work and the process that ensues mentally and physically. It can be a very helpful determinant as to whether you really want to emotionally invest in supporting an artist through collecting beyond the transactional aspect.

A lot of beautiful and very personal anecdotes live in my head when it comes to interaction with artists over my years of collecting.

The Art World

What do you think is the art-world pet peeve?

One of my largest pet peeves in the art world is the sometimes unfair and myopic way in which lazy journalism presents contemporary art from the African continent as ‘speculative’. I think that this can be reductive description and often stems from the fact that the market is understandably nascent and new. A sentiment shared by me and many others is the full knowledge that artists and art from the continent is here to stay and worthy of being taken seriously—as it should be.

Who inspires you the most in the art world?

I think my dear friend and architect David Adjaye is someone who truly inspires me within the art world at large and for many reasons. An artist in his own right, his relentless support of institutions and initiatives, like Noldor, built on empowering emerging talent within the subculture is something special. He was responsible for the design of Ghana’s inaugural pavilion at the Venice Biennale, which was a very proud moment in the country’s cultural history. Adjaye continues to be a silent but potent force for good and has played a major role in the creating pathways of some of today’s most recognized African Contemporary artists, like Gideon Appah, Amoako Boafo, amongst many others. He is, for me, a leading example of what true mentorship and community-thinking represents.

African contemporary art

How is the art scene and collecting scene in Ghana?

The art scene in Ghana is one of the most explosive and engaging spaces in the world when it comes to artistic prowess from the region. There is a new dawn of creative institutions, galleries, collectives and residencies rising to the occasion to offer artists the needed infrastructure to thrive.

However, though there is an increasing shift in interest from HNWIs, the collecting class in Ghana is still relatively small compared to other African countries like Nigeria and South Africa. Majority of the collectors acquiring Ghanaian artists are essentially foreigners, but I do trust that with organic increased awareness and visibility, there will be further growth in the interest by locals shown in investing more time and attention in contemporary art.

Can you name three emerging African/African diaspora artists who should be on our radar?

Jem Peruchinni, Maku Azu and Turiya Magadlela are three artists in particular who could go in many directions with their practice— exciting to see how their careers unfold this year.

What are you especially excited about in regard to art in 2023?

I am very excited about the different ways in which emerging artists from Africa are reaching new audiences. A wonderful example of this is the opportunity I have had to curate the first African Contemporary Art exhibition in history at Sotheby’s Tel Aviv. It is a beautiful milestone which earmarks significant progress surrounding the ever-increasing global interest in art coming from the continent. This is the future, and I am so humbled to be a part of it.

Related: Noldor Artist Residency

Instagram: @okuntakinte

A selection of artists Joseph collects:

Derrick O. Boateng

Edoardo Villa

Elizabeth Sakyiamah

Kaloki Nyamai

Prince Gyasi

Seni Awa Camara

Zizipho Poswa

By Ricko Leung