Having started collecting contemporary art in 1992, Patrizia Sandretto Re Rebaudengo was not satisfied with only owning the artworks, but she also went on to establish the Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo in 1995, in order to share her art collection and passion with the public. Then, in 2002, the Fondazione set up an exhibition space in Turin. Nowadays Patrizia Sandretto Re Rebaudengo is undoubtedly one of the most influential Italian women collectors, with an art collection of more than 1,500 contemporary pieces. She owns works by Maurizio Cattelan, Ian Cheng, Berlinde de Bruyckere, Sarah Lucas, Mark Manders, Charles Ray, Cindy Sherman, Rudolf Stingel, and Adrián Villar Rojas, just to name a few. Moreover, she sits on advisory committees or councils of various art museums and organisations. The Fondazione also expanded to Madrid in 2017.

After the last encounter at The Private Museum Conference (2018) in Hong Kong, LARRY’S LIST had the pleasure to meet and speak with Patrizia again at the opening of her latest collection exhibition at MO.CO in Montpellier, France. Recounting her journey of art collecting and developing the foundation with its multi-faceted projects and programs, she talked about the Sandretto Re Rebaudengo Art Park since 2019; the theme of the body for the current exhibition at MO.CO; why David Hammons is on her wish list; why art education is important; her advice to other collectors who may be thinking about building a private museum or art foundation; and the upcoming programs by the Fondazione to look forward to in 2022.

Background

What is your motivation behind setting up an art foundation back in the 1990s?

I grew up among old paintings and antiques. In 1992, during a journey in London, I discovered contemporary art. That trip to London was fundamental. I visited many museums, galleries, and above all, I started to get to know the artists, to visit their studios and to establish an authentic relationship with many of them. Meeting these artists opened up a whole new world for me. When I started collecting in 1992, my curiosity and passion led me to visit many museums and cultural institutions abroad.

The desire to share my collection, to support young artists, and the lack of institutions and public museums dedicated to contemporary art in Italy were definitely the main reasons that led me in 1995 to establish the Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo: a non-profit institution, which works as an observatory on art and the artists of today.

The Fondazione works with the new generations of artists, critics, and curators. We investigate all disciplines in contemporary visual arts and organise exhibitions, a residency programme for young international curators, the StellaRe Prize honouring women, talks, seminars, courses on contemporary art, as well as workshops for children, for people with special needs, and guided tours.

I always thought of the Fondazione as a place for active dialogue and constant creation of content.

The art foundation encompasses a museum space. Why is it important for you to share your art collection with a wider public?

From the beginning, I understood that I wanted my collection to be visible and accessible to everyone; I didn’t want to keep it in storage. For this reason, I decided to show part of the British collection in a former family industrial space in Turin and at the Galleria Civica in Modena in 1994. Right after, I set up the Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo, also in order to show my works (the works I collect) as much as possible.

I have no secrets. The entire collection is always available for the Fondazione. This opens a direct dialogue with the most important international institutions that are devoted to contemporary art. In this way, my collection travels, in Italy and abroad, thanks to the loan of single artworks and to the realization of shows that present aspects and themes of the pieces on which they are built. First and foremost, I felt a strong need to support the artists and to build a space for them and for the public. I began to realise the desire to share my collection with a wider and more diverse public. I never thought of the collection as something to be kept hidden in a vault.

One of the main objectives of the Fondazione is precisely to bring contemporary art closer to an ever growing audience — a goal that the Fondazione pursues both with regard to the adult public and especially in relation to children and young people through the Educational Department.

Why did you choose the two current locations for opening the venues of the foundation there?

In 1997, we opened Palazzo Re Rebaudengo, in Guarene, a small village near Alba, nestled among the hills of the Langhe-Roero, home of the white truffle, Barolo and Barbaresco wines and a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Palazzo Re Rebaudengo is a historical 18th-century mansion, adapted for use as an exhibition space for contemporary art: it was redesigned as an exhibition center, with a project that preserved the original architecture, bringing close interaction between past and present.

In Guarene, we aim to bring art back into nature, close to people, in villages and therefore in a landscape and housing dimensions far from the cities, in public spaces and in outdoor places where everyone can see the works and enter a relationship with them.

In September 2002, the Fondazione opened its current headquarters, a 4,000 square metre center for contemporary art in Turin, designed by architect Claudio Silvestrin. The Turin site is a newly built museum in a neighbourhood that bears witness to the city’s industrial past and its transformations. The building used to be a factory for car rims, stands in front of a public garden and is a neutral and linear structure. Inside, it is completely white, and the space can change shape according to the wishes of the artists.

With a gallery space of over 1,500 square metres, a bookshop, auditorium, educational room, cafeteria designed by Rudolf Stingel and Spazio7, a Michelin-starred restaurant, the center is a flexible structure that presents exhibitions bringing together artists, as well as operating as a meeting place for a variety of audience, and an experimental platform for contemporary culture.

When I first saw the place in Turin where the Turin venue of the Fondazione would then be built, I thought this is where my “Serpentine” will rise! In fact, I will never forget my visit to the Serpentine Gallery in 1992 as it was the moment when I decided to start my collection. The Serpentine became a model for me, a sort of a guiding light.

And later on, how did you decide to also set up a foundation in Madrid?

In 2017, I established Fundación Sandretto Re Rebaudengo Madrid. I had been thinking of extending Fondazione’s horizons since a long time, considering the possibility of setting up a new project outside Turin, another place where carrying on our exhibitions, productions, activities and initiatives. I evaluated various possibilities and different locations, both in Italy and abroad. The choice of Madrid lies first of all on my love for Spain, that I consider my second homeland.

What are the missions of the Fondazione?

The Fondazione has three main aims: to support and promote artists, showing their artworks, commissioning and producing new works, organising exhibitions, providing space for the exhibition of artists; to educate and widen access to contemporary art; and to create partnerships with national and international institutions.

What are the ways to achieve these missions?

The commission and the production of new works are vital to the Fondazione and to our goals. Commissions are developed in different ways — sometimes we invite artists to present projects based on curatorial concepts that we may be working on for our exhibition program at that time, as we have done with many artists. For example, our collaboration with Ian Cheng, which we decided to support through the production of the first chapter of a trilogy of media-based works, with Adrian Villar Rojas, with the exhibition “Rinascimento” (2015) and Berlinde de Bruyckere with an immersive environmental installation.

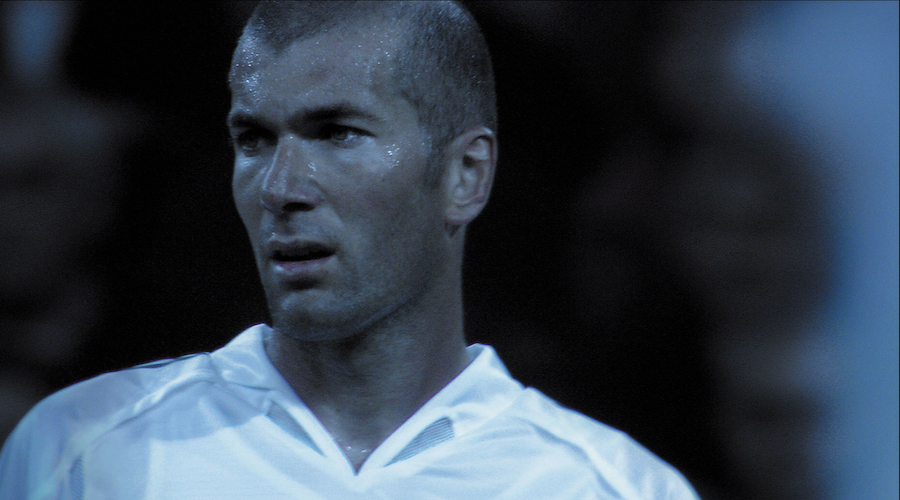

A second way of supporting the production of artworks is when artists ask for our assistance in giving life to their works. For example, with Douglas Gordon and Philippe Parreno for “Zidane – A 21st Century Portrait”. The artists wanted to make a portrait of someone they considered a true 21st-century icon: the football player Zinedine Zidane. Their idea was that a contemporary portrait should not be “oil on canvas”, but a video instead. This work was presented at the Cannes Festival in 2006. We worked in a similar way for Doug Aitken with “New Ocean”, in collaboration with the Serpentine Galleries. Sometimes we get involved in the production or co-production of works to be featured in major international exhibitions, such as the Venice Biennale, which have included projects by Doug Aitken (1999), Luisa Lambri (1999), Steve McQueen (2007), Goshka Macuga (2009), Meris Angioletti (Stanzas, 2011), Ragnar Kjartansson (2013), Jason Moran (2015), and Alicja Kwade (2017). We also produced a project with Wael Shawky for Documenta 2012. We produced works by Ed Atkins (UK), Marwan Rechmaoui (Lebanon) and Elena Mazzi (Italy) for the Istanbul Biennial (2015).

I have always appreciated artists who are curious and open to even the most complicated and less traditional media. I had an instinctive inclination in collecting photo and video installations at the time when they were still not a widespread phenomenon. Today, I am still interested in time-based works, as shown by the project we carried out together with the Philadelphia Museum. “The Future Fields Commission in Time-Based Media” is an initiative that was jointly promoted by the Philadelphia Museum and the Fondazione. It is a platform created to support the production and co-acquisition of works by new, engaging artists of video, sound and performance arts. Within this project, works by Rachel Rose and Martine Syms were produced, and we will produce the work by Lawrence Abu Hamdan in 2022.

The second aim of the Fondazione is to educate and to bring an ever-wider audience close to contemporary art. The Education Department is fundamental for the Fondazione, and more than 30.000 children and students pass through our doors every year (unfortunately not last year) to take part to our activities, courses, and workshops. From the beginning, to interact with our audiences and visitors, the Fondazione adopted an innovative form of relationship: the art mediation. Every day in our exhibition space the art mediators are there to facilitate the relationship between the visitors and the artworks. One of the Education Department’s main aims is that of making the museum an accessible place for all visitors, and especially that with special needs (blind, deaf, Parkinson, and so on.) Regarding training, since 2007 we run a Young Curators Residency Programme (Turin and Madrid). A project with the central objective of creating a network between foreign curators and Italian (or Spanish) artists.

Our third aim is to create partnerships with national and international institutions. It is very important to strengthen collaboration and dialogue with other art institutions around the world. And at the same time, when possible, I am happy to loan works to other art institutions and museums — which is important for my Fondazione. I am personally involved in projects with various institutions: Tate International Council in London, New Museum Leadership Council, MOMA International Council, Advisory Committee for Modern and Contemporary Art Philadelphia Museum, Bard College in New York, RAM in Shanghai, only to name the best known.

The collection

How many artworks do you own and how many of them are displayed in the museum? What are the criteria to decide what from your collection to show in the museum?

At the beginning, my collection followed five themes, each exploring aspects of artistic production from the 80s to today: British art, the Los Angeles art scene, Italian art, female artists, and photography. My collection is almost entirely contemporary. Photography is the only section that has historical depth. I have around 3000 historical photographs dating from the 1839, which retraces the history of Italian landscape. In recent years, my interests have extended, and I can no longer categorize my collection by nationality, genre, or ways and means of expression.

The collection includes more than 1,500 works, but they are not shown on a permanent basis at the Fondazione’s venues in Turin. Here we organize temporary exhibitions, sometimes devoted to the collection, which are organized around a topic or theme. The collection also travels a lot, with focused presentations like the current one in Montpellier. Recently, we inaugurated a new project devoted to the collection, which is an open-air sculpture park, and there we show works and new commissions on a permanent basis.

In 2019, before pandemic, we created the Sandretto Re Rebaudengo Art Park on the San Licerio Hill in Guarene. It is a place, with free entry, where Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo presents outdoor installations, among the rows of a Nebbiolo vineyard – from which we produce our rosé wine – and also willows, oaks and the wild greenery of an ancient wood. The installations are created by recognized artists, both in the Italian and in the international scene. In the Sandretto Re Rebaudengo Art Park, the sculptures dialogue with nature and enter into harmony with the landscape. For this special place, the artist Mark Handforth represented a concept of circular economy creating two large benches by using wood from a cypress that fell naturally, after growing on the hill for over a hundred years.

Other artists with permanent artworks include: Ludovica Carbotta, Manuele Cerutti, Carsten Höller, Paul Kneale, Wilhelm Mundt, and Marguerite Humeau.

Where else have you shown your art collection publicly?

Throughout the years, we have shown the collection in many institutions in Italy and abroad, and I think this is really a fundamental part of the work of the Fondazione’s work and the intention to make the collection shared and widely visible.

I would just like to name you a few: Sala de Exposiciones del Canal de Isabel II in Madrid; Domaine de Kerguéhennec in Bignan; Hara Museum of Contemporary Art in Tokyo; IVAM in Valencia; Salle Quai Antoine in Montecarlo; Museo Benaki in Athens; Ciudad Grupo Santander in Madrid; Whitechapel Gallery in London; Kunsthalle in Krems, CoCA in Torun; meCollectors Room in Berlin; Fundaciòn Francisco Godia in Barcelona; Centro de Arte Contemporaneo in Malaga; Maison Particulière in Bruxelles; Centro de Arte Contemporanea in Quito; Sheffield Cathedral; Rockbund Art Museum in Shanghai; Touchstones Rochdale Art Gallery; MACRO in Rome; and most recently MO.CO in Montpellier.

Currently you are having an exhibition of part of your collection in Montpellier. Why this theme about the body?

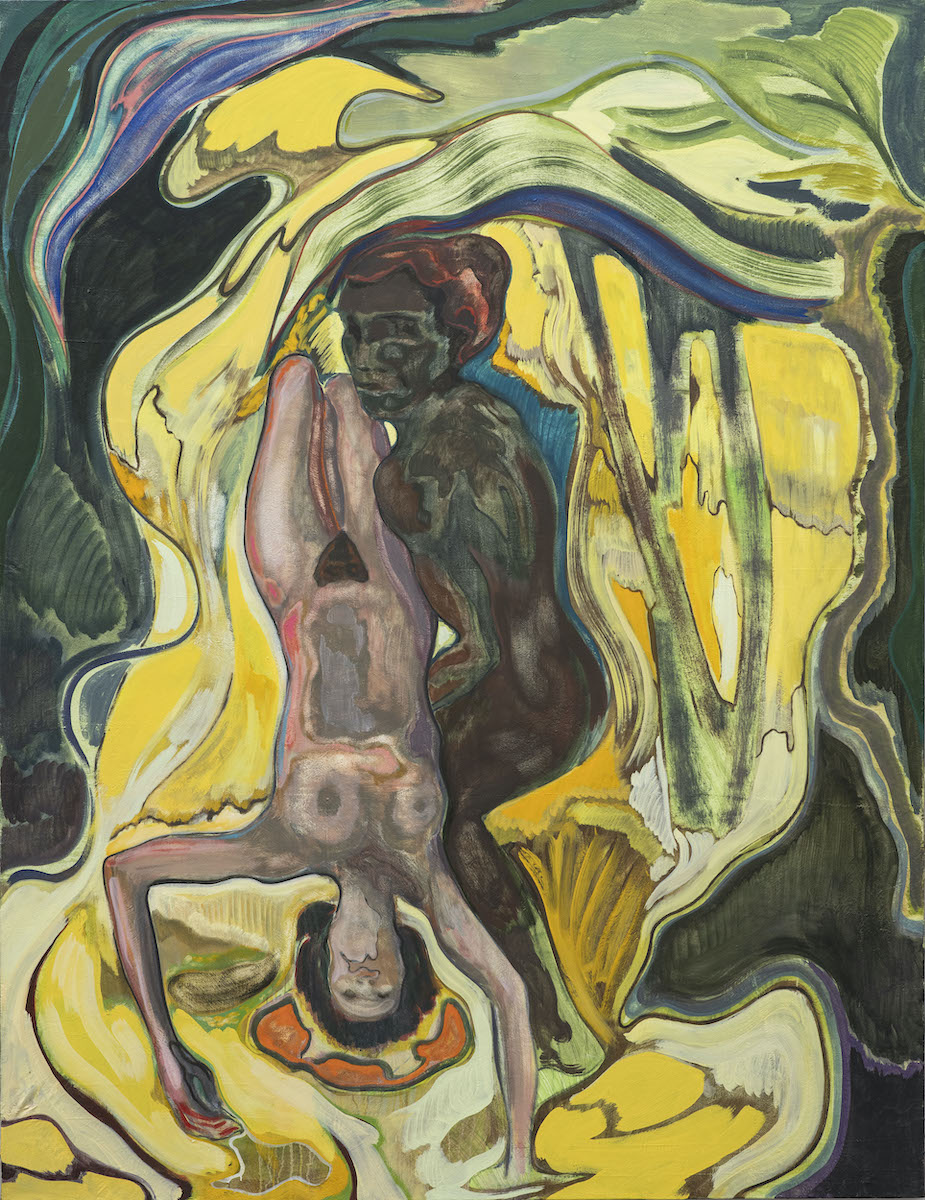

The topic was chosen by Vincent Honoré and Caroline Chabrand, respectively director and curator of the MO.CO, and I found it very relevant today, right at the center of the current debates, especially in regard to the transformations of the human vis-à-vis with the technological progress. This topic resonates a lot in my collection, both in earlier practices that dealt with identity and representation politics, like in the works by Cindy Sherman, Barbara Kruger, Senga Nengudi or Catherine Opie; and in most recent ones which address new notions of materiality and corporeality, like in the works by Ed Atkins, Josh Kline and Ian Cheng.

Also, the vulnerability of the human body, after almost two years of pandemic, is quite symbolic of the times we are living in. From this point of view, the idea of anatomy as a science of dissection seems quite fitting, in that it evokes an analytical approach, the body as an object of study, of scrutiny, of illness and healing, of violence and beauty, which I see addressed in works by Zoe Leonard, Berlinde De Bruyckere, and Sanya Kantarovsky.

How much did you involve in curating this exhibition? And how has been the experience of making this exhibition so far?

The exhibitions of my collection usually develop through dialogues between the curators of the hosting institution, myself and the Fondazione’s curators. We know well the collection, while they propose ideas, topics, new perspectives through which the collection can be interpreted and presented, and I always welcome and enjoy these dynamics. The curating process generates through an exchange of proposals, suggestions, feedback, but it is very important for me to let the curators develop their own reading of the collection, which is always enriching my own view of it, and opening up new areas of enquiry. It’s also an open process because these interpretations are the result of different places and times, so they continuously move and update the critical reading of the collection.

Even for myself, seeing the collection displayed in new places and through new ways of thinking about it, is always an opportunity to read and re-read it through a different lens.

The programming

Your foundation is also active in art education. Why do you think it is important?

Education is a priority for me. Our educational work in Turin benefits children from 2 years old, teenagers, art academy and university students, teachers, people with disabilities, families, and adults. We firmly believe in the idea of an accessible museum, that enables each visitor to take advantage of the cultural content we offer. This is the reason why we have so many different projects, involving so many kinds of audiences: family Sundays every month, free workshops for adults on Thursday evenings, intensive workshops for teenagers and university students and special projects for infant and primary schools all year long, permanent activities for people with disabilities (especially with the Italian Union of Blind People) and e-learning projects. We believe that understanding art is a vital component of every person’s education and development — contemporary art often uses unconventional methods, media and messages that push the boundaries of traditional art forms.

What motivated you to set up the Young Curators Residency Programme in both Torino and Madrid? What kind of support and resources do you share with these young curators?

One of our missions is to educate and to widen access to contemporary art, also through the formation of the young generation. This is the reason why from 2007 the Fondazione in Torino has established a very important project: The Young Curators Residency Programme.

Every year, three young curators (selected from the most prestigious curatorial schools) from the world are chosen for a 4-month residency: they travel around Italy, meet artists, curators, and museum directors, and visit artists’ studios and galleries. The group curates a final exhibition, with the work of the Italian artists they met during their trips. The residency has the dual objective of developing the professional and intellectual skills of young curators in the early stages of their career, together with that of taking Italian contemporary art into a more international context.

Two years ago, the Fondazione created the Young Curators Residency Programme Madrid, which is the Spanish equivalent of the Young Curators Residency Programme operating in Torino.

Our objective for the coming years is to open our program to other parts of the world. With this in mind, we have reached agreements with Shanghai’s Rockbund Art Museum in selecting potential participants from Asia with an executive committee set up for this reason.

What are the upcoming programs and projects in 2022? Which ones we definitely should not miss out?

We are still working on our program for the upcoming year, it would be complete soon.

In Turin, in April 2022, a presentation of new works by American painter Sayre Gomez whose work is inspired by the urban landscape of Los Angeles.

Then, we will display an exhibition for the third season of our Verso project and in June, as the final chapter, Dutch artist Jonas Staal will present a new iteration of his on-going project of utopian training camp.

In November, a major new solo presentation by Dubai-based artist and audio investigator, Lawrence Abu Hamdan, selected as the biannual award winner of the Future Fields Commission in time-based media.

Moreover, in Turin we will open a solo show of the Romanian artist Victor Man.

As for the previous programs, we will host the final exhibition of our Young Curators Residency Programme both in Guarene, for the Italian edition, and in Madrid for the Spanish one.

In Madrid, in February, we present new works by the acclaimed painter Michael Armitage, developed in response to masters of the Academia’s collection, including Goya.

Besides, a major project I am very keen on will take shape in a number of cities in Spain.

Visions for the Fondazione

What was your happiest or most memorable moment since your foundation has been set up?

The inauguration of the Fondazione’s two sites, in Guarene and Turin, is certainly one of my best memories. I vividly remember the overwhelming emotion of those days — the fulfilled desire to finally share so much work with people, artists, friends from all over the world; and seeing such a fundamental project for my life and my vision realised with my own eyes. It is incredible now to think that it was only the beginning…

On the other hand, I am not joking when I say that one of my greatest joys is every day when I see so many children and young people visiting our exhibitions and participating in the workshops designed by our Education Department. Seeing them in the halls having fun and interacting with the artworks makes me feel really blessed, passionate, and satisfied.

What are on your wish list regarding artworks and your museum?

Generally, I prefer art that is more political and social. Sometimes, I have brought out of impulse, but the works have been acquired to become part of a structured collection.

Thinking about the artworks of my dreams, the works I have forgotten to buy immediately come to mind. For example, I’ve never bought David Hammons. I’ve always been interested in Hammons’ research; I like his sculptures that dismantle the stereotypes of capitalist society. For some reason, though, every time I’ve tried to buy one of his works, I haven’t succeeded. I would definitely put him on my wish list.

It is even more difficult, if possible, to imagine a wish list regarding my institution. Instinctively, I would say I wish more space for artists to exhibit and to show my collection in ever different ways.

What do you think are the key elements that determine the success of a private museum?

Two keys are essential for me. The first concerns the responsibility that the private sector must assume with respect to artists, visitors, and the community. Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo is a private, non-profit institution that follows the guidelines of a public museum. It respects international standards regarding the professionalism of the team, the criteria for exhibiting and preserving works, the services for the public, the educational offer for schools and families, and accessibility for all.

The second key concerns experimentation: a private institution is more flexible than a public structure. This flexibility can and must translate into innovation, for example regarding the ability of creating new models, the timeliness of the introduction of new practices. This is what we did in 2002, for example, when we opened the Fondazione’s venue in Turin, being the first in Italy to offer a cultural mediation service. Inspired by the French model, we adopted a methodology that transforms the exhibition into a space for conversation and reflection, replacing the traditional figures of attendants or guides with mediators, capable of providing information, listening to the opinions of visitors and, above all, giving them the floor.

What are your visions for the Fondazione in the next five and ten years respectively?

An agora, a square, a park, a garden. These are my guiding images, the ones that inspire and guide our institution today and our project for tomorrow. These are concepts and forms that define the relationship between contemporary art and public space, and therefore the relationship with the city, the territory and the community. Inside or outside the exhibition space, the museum of the next decade will, in my opinion, have to intensify its civic and social role. In the Fondazione, we have started to do this mainly with two projects. The first is the Sandretto Re Rebaudengo Art Park, in Guarene, a park of large-scale sculptures. Some are part of my collection, as in the case of “Vehicle (Amphibian)” by Carsten Höller, others are site-specific productions, as in the case of “Rise”, a spectacular work conceived by French artist Marguerite Humeau. The Park is always open: it is the place where the public can explore and experience the nature-culture relationship directly.

As a second focal point, we aim to establish a meaningful dialogue with young people, artists and audience. That’s why we designed Verso, a programme dedicated to young people between the ages of 15 and 29, ideated by the Fondazione and the Youth Policy sectors of the Piedmont Region and the Italian Government. Started in June this year, it will run until July 2022, offering exhibitions, workshops, research grants, public programme, in a real training of the younger generation in democratic debate and political and critical thinking.

What is your advice to other collectors who may be thinking about building a private museum?

Firstly, I suggest travelling around, visiting public and private museums and foundations in your own country, and then to widen the range to the international context. This is what I personally did before opening Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo. Start with an idea, an image, whether clear or still undefined. In all cases, be willing to change it, moved by positive or negative examples. I think it is very useful to analyse the existing structures and organisations, to let them inspire us, but also to ask ourselves what is missing, what we could add by making our own private institution.

I believe that art patronage today is defined by supporting artists’ careers and practices, providing them, for instance, with opportunities for exposure, keeping in mind that the end goal is their success, and the fulfillment of their artistic research. It is necessary to be clear that the ways of being a patron change with the generations: the collecting and philanthropic landscape today is not the same one as in the 1990s when I started collecting. Nor is it the same as canonical arts patronage in the 1500s or 1800s.

Indeed, I’m fairly convinced that private funding will play an increasingly important role in the commission of installations and sculptures. This is not a novel idea, as this was the standard throughout Renaissance and the whole period that the Church was one of the biggest art patrons, but it is experiencing renewed popularity.

Patronage will also remain an important component of public institution funding, although over the past 10-20 years there has been a shift, whereby prolific collectors prefer to establish their own exhibition space, rather than funding a public institution. If this trend continues, and relationships between private and public institutions are not managed well, I believe the unbalanced landscape will present a new challenge; however, if they are well managed, I believe they will present interesting opportunities, possibly better reflecting the globalised art world we currently live in.

Going forward, I believe patrons will be increasingly able — and willing — to help building bridges across diverse creative industries — art & fashion, art & design, art & jewelry, etc. These collaborations will provide interesting opportunities by creating an additional revenue channel to actively support artists in the production and development of their ideas and vision.

Furthermore, I think that art patronage will also have to face the fact that, overall, collectors tend to be focused on a very limited fraction of artists. The challenge will be to guarantee an increased diversity of voices, to grant opportunities to an extended and diverse range of backgrounds. This means that we will need patrons who are not only interested in following trends, but who have the courage to explore different points of view. Truth be told, in the last few years, it does seem like things are moving in this direction, with a heightened attention toward diverse ethnicities and gender diversity.

Current exhibition: <<Bodies at Stake>> Collection Sandretto Re Rebaudengo, MO.CO. Hotel des Collections, until 13.2.2022

Related: Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo

Instagram: @fondazionesandretto

By Ricko Leung