In the village of Susch in the Engadin valley in Eastern Switzerland, Polish entrepreneur and collector Grażyna Kulczyk has an ancient monastery and brewery transformed into her private museum, Muzeum Susch – her magnum opus of her life as a patron of the arts as she describes it.

Grażyna Kulczyk shares with LARRY’S LIST why she has a specific interest in women artists as the focus of her collection and part of the focus of the museum; how she attempts to challenge the dominant mode of thinking that ‘a private art gallery/museum is of less quality or impact than a public institution’; what is “Slow Art” and why she wants to support that notion with Muzeum Susch up in the mountains.

Background

What is your motivation behind opening the Muzeum Susch?

I have been engaged in various art activities for the last 45 years. Already as a law student I began giving community lectures about contemporary art in my hometown of Poznań, where I started to become involved in the art scene. Since then, I have supported hundreds of art projects, later introducing my life motto of ‘50% art, 50% business’, to structure my engagements into coherent actions. This motto specifically defined Stary Browar: the 8-hectare former brewery buildings I restored in the center of Poznań and opened in 2003. By placing dedicated exhibition spaces and a theater at the heart of a commercial complex, it allowed people to see and discover art in public spaces where they might not always expect it or engage with it in the same way. With Muzeum Susch here in the Swiss Alps I have decided to focus on art only, but again in the broadest sense. The programme is made up of five pillars – exhibition spaces, a research institute, a choreography center, artists’ residency and an annual academic symposium – that I hope will introduce and encourage new ways of thinking.

Why is it important for you to share your visions in contemporary art with a wider public?

As described above, beginning from my student days I was motivated to teach and inspire others in matters relating to art. I have a desire to be active and to shape the art world from my position, and also to challenge the dominant mode of thinking that a private art gallery/museum (too often misinterpreted as a vanity project) is of less quality or impact than a public institution. Art has come a long way through the Anthropocene, being displayed and viewed in so many ways – from religious to secular, from intimate and humble Dutch bourgeois interiors, from palaces to grandiose museum buildings; and now being democratized by urban museum as super-machines as well as InstaArt. I aim to be a prominent voice in the discourse and try to find, together with some other museum founders, an alternative path, which is often now defined as “Slow Art”. This speaks not only to art aficionados, specialists, collectors but to anyone who want to take their time and devote much more to observing and truly thinking about the art they see. This is an effect I hope to achieve with Muzeum Susch up here in the mountains.

Why do you have a specific interest in women artists as part of the focus of the museum?

Works by women artists are a core theme of my collection. It is an affinity that perhaps stems from my own experience as a woman in the male-dominated sphere of business, where I often had to fight for my voice to be heard.

I simply believe that, to date – even though some progress is being made – women artists have not been positioned accurately across art institutions. I set out to correct this through the programming at the museum, but equally aim to give visibility to all artists whose work – perhaps for political, social, or economic reasons – has not received appropriate recognition. My ambition is to create a productive dialogue among actors who have challenged, or even changed, the dominant canon of art history. Some people say that nowadays the female focus is almost overrepresented in various exhibitions and publications – but there is so much to be corrected in history and the statistics are still miserable.

Why did you choose this location for opening the museum? And what attracted you of the former rural monastery and industrial brewery building?

My plans for establishing an art museum had actually begun more than a decade ago.In 2008, I commissioned a museum project in Poznań by Tadao Andō, which was intended to neighbor the Stary Browar complex, where I had been running an exhibition program since 2003. After the local government declined the opportunity of working together, I moved on to planning a museum in the capital, Warsaw. However, the City of Warsaw was also not committed to the private-public project I proposed, even though it would have been funded entirely by me. My discovery of the site in Susch came by chance, while driving one day from my home nearby in the Lower Engadin. I had noticed a group of intriguing industrial-looking buildings, which drew me to investigate further. I started reading up on the history of the town and discovered that the buildings had once played a vital role in shaping the local community and history – functioning as a point to rest and change horses on the ancient pilgrim route to Santiago de Compostela; a place related to a historically important Reformation debate held in the neighboring church in 1537; and a site of trade (the monks were active beer producers). It became clear that such a remote location with a rich cultural history was the perfect place for the kind of activity I had in mind –a museum with a disruptive outlook and approach to the future that allows for contemplation (and by this I don’t mean to disengage from the world but to allow for thinking with a certain distance from the busy and bustling centers).I therefore decided to shift all my efforts and activities to Susch and create the complete cultural institution I had dreamt of for years.

What were the challenges in revitalizing the buildings? And how does the final architecture facilitate or echo with the exhibition of contemporary art?

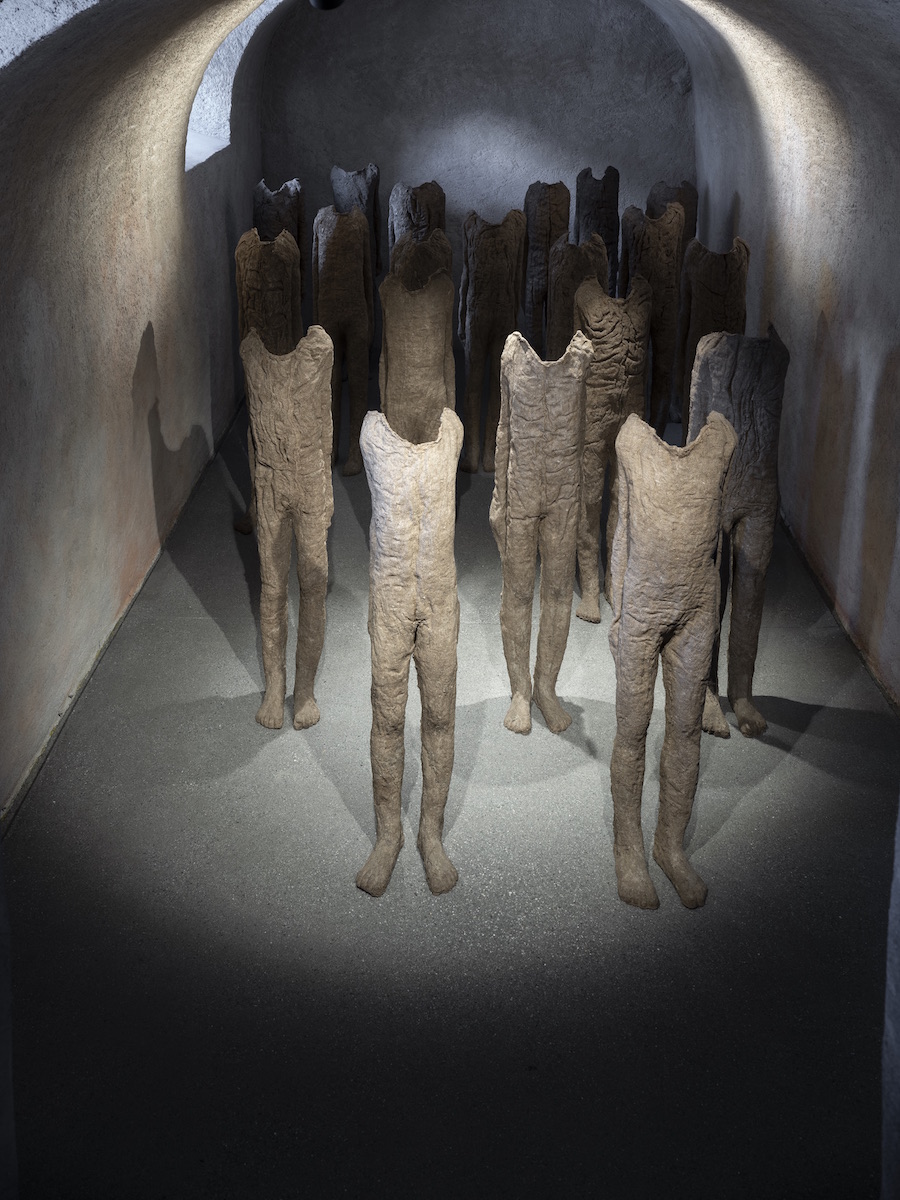

The old part of the village of Susch is under a preservation order, which we had to be very mindful of in the renovation and expansion of the buildings. I chose the architects, Lukas Voellmy and Chasper Schmidlin, quite specifically for this reason, as they have great local sense and expertise in the specific style of building in the area through which we were able to introduce minimal but decisive architectural interventions. Retaining the history of the building as part of the design was very important to us, so we worked closely with local restaurateurs to use and re-emphasize some of the existing old structures. In order not to disrupt the fabric of the village, the main expansion of the museum took place underground, which also serves to connect the building directly to the landscape. One of the many distinctive features is its atmospheric underground grotto spaces, leaving the mountain rock exposed, which remind the visitors of the landscape outside. In one of these rooms – being tagged by some visitors as the ‘weeping room’ –there is even a natural water source running through the rock, which historically would have been used by the monks for cooling and brewing the beer. Rather than work against nature, we have chosen to incorporate it into the design of the building, reminding us of its greater force over humanity.

What are the missions of the museum?

Broadly speaking, the museum’s goal is to explore the disruption of accepted power structures, bringing artists, movements and ideas, that to date have been marginalised or left outside of the canon, centre stage and giving them new opportunities to be heard. Muzeum Susch is intended not just as a vessel to show contemporary art, but also as a station for knowledge and creative production. Within our team we like to describe it as a ‘museum plus’.

What are the ways to achieve these missions?

The founding goals of Art Stations Foundation CH, the umbrella responsible for the programming of Muzeum Susch, go beyond the art exhibition programme, opening out to other perspectives and voices. The Foundation will continue running its multi-level performative programme, that launched 15 years ago at the center of Stary Browar complex in Poznań, Poland and promoted experimental choreography and dance productions from around the globe. This has extended its activities to Switzerland under the name of Acziun Susch.

An equally important part in the activities of the foundation will be played by the programme of residencies, aimed at artists, curators, writers, choreographers – Temporars Susch. The annual discursive symposium, Disputations Susch, has already had its first two editions since 2017 and will convene again this October 2019, themed on ‘Magicians of the Mountain’ in reference to the 90th anniversary of the Davos Disputation between Ernst Cassirer and Martin Heidegger. Finally, it includes the activities of Instituto Susch, launched last year in collaboration with Chus Martinez and Institut Kunst, Basel, which continues to investigate key issues relating to the role of women in the arts, culture and science.

Collection

How much proportion of your collection is shown in the museum?

Crucially, Muzeum Susch is not intended just to house and show my collection but instead the artistic program draws from and expands on key themes within it. As the first example, the inaugural show, ‘A Women Looking at Men Looking at Women’, curated by Kasia Redzisz, draws on the significant focus on women artists at the core of my collection. The show borrows key works from my collection (amounting to 40% of the exhibits) and mixes these with wider loans from other museum collections, galleries and artist estates. The proportions will vary with each future exhibition.

What are the criteria/How do you decide what from your collection to show in the museum?

The intention of Muzeum Susch is to show works beyond my own collection, although guest curators are invited to draw inspiration from themes within it. This will be decided collaboratively with each new curator of future exhibitions. Each temporary exhibition will bring together works and loans from wide-ranging sources. I do believe that showcasing works from my personal collection in various contexts and in juxtapositions will highlight their resonance within a wider cultural debate. Introducing new commissions was also important to me as one of the goals of Muzeum Susch is to encourage new ways of thinking and creating, enabling artistic production.

Exhibitions and the programming

What are special about the series of permanent, site-specific installations in the museum?

The permanent installations (as we call them Installaziuns) at Muzeum Susch play an integral part in shaping the evolving character and distinctive layout of the space and seek to re-examine the notion of the ‘site-specific’. The twelve works on display communicate directly with the architecture of the building and the surrounding alpine landscape. The first of these site-specific works – Monika Sosnowska’s ‘Stairs’(2016-17) –was installed before the museum building was even completed, due to the monumental scale of the impressive steel structure that now fills the central tower of the building. Where most museums might center around a grand staircase, Muzeum Susch centers around this artwork. Another early site-specific installation was made by Paulina Ołowska, who employed the traditional Engadiner ‘sgraffito’ technique and worked with a local maestro to develop her design directly on the museums interior walls. In one of the museum’s grottos, Mirosław Bałka’s ‘Narcissussusch’ (2018) is a revolving mirrored cylinder that reflects the surrounding rock formations, flirting with time perception. Another work that is deeply integrated into the fabric of the building is made by Swiss artist, Sara Masüger who has created an immersive, ‘tunnel’ that brings the sounds of the local River Inn in to the museum as well as showing the almost biological substance of architecture. These are just a few examples of what can be realized with and within the space.

What are the highlights at the current inaugural exhibition ‘A Woman Looking at Men Looking at Women’?

The inaugural group exhibition at Muzeum Susch, curated by Kasia Redzisz, weaves the narrative of artists who, regardless of gender, have been able to challenge not only social norms but also the limitations of art and its restrictive categories. Bringing in important loans as well as select works from my own collection, the show draws attention to a number of trailblazing artists who, to date, have not had the recognition they deserve in the dominant narrative of art history, such as Alina Szapocznikow, Carla Accardi, Laura Grisi, and Helena Almeida. Women artists for decades, if not centuries, were conceived by male critics as unable to perform complex, intellectual projects. This exhibition, rather than reiterating established polemics, seeks to offer a fresh perspective on the paradoxes of the feminine. In the works on display, the female gaze predominates and shifts the notion of the female from being an object being looked at to subjects analyzing their presence.

How much do you involve in the programming as well as the curating of exhibitions in the museum?

Although each exhibition will invite a curator or artist to put together the show, it is not in my nature to refrain from playing an active role. I will always cooperate and give my feedback or input to the curators,and I think that it is always interesting to have a lively discourse when creating the exhibition. I have learnt through experience in my entrepreneurial life that collaborative teamwork usually brings the most interesting outcome as well as courage to take immediate responsibility for final decisions

CH.

What are the special upcoming programs in the next 12 months that we definitely should not miss out?

The summer show 2019, opening 26 July, will be a solo by Emma Kunz, organised in collaboration with the Serpentine Galleries, London. The last public exhibition of works by Emma Kunz in Switzerland was in 2012 at Zentrum Paul Klee, Bern. It is a timely moment to bring her back to central attention in the country of her origin. This show aims to situate Emma Kunz within a contemporary discourse, bringing this historic body of work to future generations.

Also, this summer, in July, the first research residency will bring choreographers and dancers to Susch, inviting the audience to attending rehearsals and get an insight into their practice.

In October 2019, the third annual discursive symposium, Disputaziuns Susch, takes place again; this time taking up the question: ‘What is it to be Human?’ in reference to the Cassirer/Heidegger debate in Davos in 1929. Scholars, artists, philosophers and authors will come together to discuss and debate the relationships between philosophy, politics and art.

Our first year of exhibition activity in Muzeum Susch will conclude with the opening of the third show end of December 2019, on the legacy of Carolee Schneemann curated by Sabine Breitwieser.

The magnum opus

What was your happiest or most memorable moment since your private museum or foundation has been set up?

Please bear in mind that I have set up my foundation over twenty years ago in Poland, and since then it has carried hundreds of cultural projects and exhibitions – all memorable moments for me. But Muzeum Susch is the ‘magnum opus’ of my life as a patron of the arts. I have to admit that I truly did not expect our academic research, starting at the 3rd level, and the exhibition and institution in this remote Alpine location to bring in 10,000 visitors in the first five months. It feels we have already cut a chunk right in the middle of the art cake. The truly warm and emotional reception of the museum, hundreds of remarks and conversations I have had since the opening – this makes me very happy.

What do you think are the key elements that determine the success of a private museum?

Something I have learned from my many years in business is that a collaborative approach is a resourceful tool to success. A short and direct decision-making process allows us to react in a timely fashion to recent cultural or political challenges. The collaborative approach is substantial during the creative and research phase of any project, however for the execution, it becomes decisive to convince the boards and committees alike in the large institutions.

By incorporating a wide range of voices and perspectives, the Muzeum introduces a lively and healthy sense of debate and opening up to new ideas and opinions. We are achieving this through various international collaborations that have already started, involving curators in the exhibition programming, and working with the Institut Kunst Basel on the activities of the Instituto Susch research centre.

It is also crucial to engage with a broad spectrum of people – at local, regional and international levels. The multi-faceted program of Muzeum Susch sets out to achieve this through various initiatives – from hosting art classes for local schools to broadcasting conferences run by the Instituto Susch via podcast that are accessible worldwide, even to those who are not able to physically visit the museum.

What are your visions for the museum in the next five and ten years respectively?

The planned nature of Muzeum Susch means that it will continue to evolve – it will be shaped by artists and scholars as well as the Art Station Foundation’s own multifaceted activities. I hope that it will educate and inspire people, not only in matters relating to art but to think differently in their approach to individual, economic and political proceedings. I would like the Muzeum to become a point of reference – both as a site of cultural pilgrimage and as a new model for art and ideas. Through art, I want to raise discussion on topics which really matter to us as humans.

Related: Muzeum Susch

Instagram: @muzeumsusch

This ‘Private Museum Insights’ editorial series is born with the support of Phillips, a partner of THE PRIVATE ART PASS.